An Interview with April Harrison and Tricia Elam Walker

“My Art Room Becomes a Sanctuary”

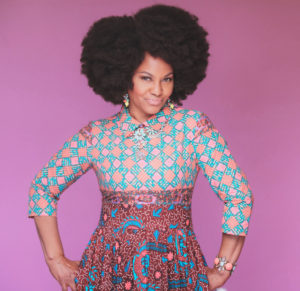

Meet April Harrison

April Harrison is a fine artist and illustrator based in Greenville, South Carolina. This interview by Nadine Pinede was edited for length and clarity.

NP: I loved your virtual read-along of Nana Akua Goes to School with author Tricia Elam Walker for Politics and Prose Bookstore. You’ve been a mixed media artist for years, but only recently became an illustrator. How did that come about?

AH: Well, you know, Nadine, I was minding my own business, doing my fine art, and boom! No, really, in 2016, I received an email from Penguin Random House, and they wanted to know if I’d be interested in illustrating a children’s book. They sent me the manuscript and said, “Read it. Decide if you would like to illustrate it.”

The catch was they wanted me to illustrate a full page. I thought, “Okay, that’s so easy.” Then it came back again. They said, “Well, wait a minute. We want you to show one of the action pages.” They were trying to make it a little tougher, I guess. So I did a walking scene, when the mom and son were walking home from church. They saw it, they loved it, and they hired me as the illustrator.

NP: That first picture book you illustrated was What is Given from the Heart, written by the late Patricia McKissack, winner of the Coretta Scott King-Virginia Hamilton Award for Lifetime Achievement. You won the John Steptoe Award for New Talent for it. What a debut!

AH: Yes, it was an extreme honor to be recognized as a contributor to the up-building of our people, culture and humanity.

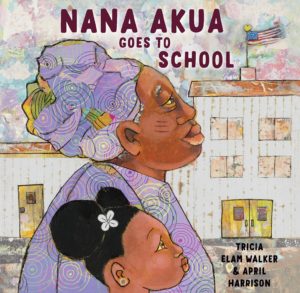

NP: Nana Akua Goes to School is your second picture book. What was it like bringing Tricia Elam Walker’s words to life?

AH: She’s an amazing writer! She writes wonderful novels and articles, and this is her first children’s picture book. The story itself was so inspiring: the way she writes, how she considered the feelings of Zura and how Zura related to her grandmother. This sweet story was the reason I accepted the manuscript. I felt a purity that made me say, “Yes, I will illustrate this book. I love it.”

NP: Tricia said it takes a village to create a children’s book. What role did Regina play in that village?

AH: Regina is a great advisor. She’s involved in the total process from beginning to the end. She’s very hands-on, which is a great indicator of how much she cares about the success of not only the book but the client she represents.

NP: What did you most enjoy about working with Tricia?

AH: I love her energy! She’s easy to communicate with, very gracious and a great gift-giver! When she found out that I loved the Gye Nyame Adinkra symbol, she gifted me with a ring and bracelet with this symbol. Tricia is just good people.

NP: That’s wonderful. Did you communicate with Regina as well?

AH: I did. She was my liaison. She’s connected to some very important people in Ghana. Having that connection made sure that we were applying the correct tribal markings to Nana Akua’s face. We were so grateful for Regina’s input as it was our goal to represent the Akan people with dignity, respect and honor.

NP: Making music together could be a metaphor for this process. You’ve said that when you do your fine arts, you’re more in your own head. Does music play a role there too?

AH: Absolutely. My art room becomes a sanctuary, and in this sanctuary I mostly listen to gospel, jazz and some classical music, like Ludwig Göransson, who composed the score for Black Panther. The music is selected based on the message I’m trying to convey through the painting.

NP: Do you have some names for those of us who’d like a playlist?

AH: In gospel, I listen to Sean C. Johnson, Mali Music, Jonathan Taylor, Lexi, Lisa McClendon, and Koryn Hawthorne. In jazz, there’s Coltrane, Byrd, Miles, Christian Scott aTunde Adjuah, Robert Glasper, and Ashley Henry.

NP: Did your grandmothers inspire Nana?

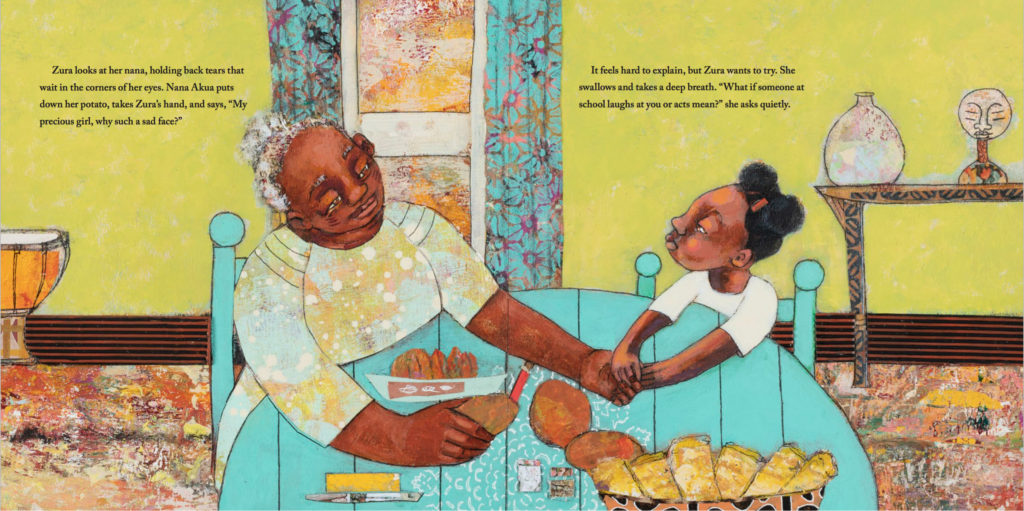

AH: Yes, by their loving spirits. I wanted to just show a beautiful grandmother with loving eyes, a gentle spirit- someone any child would want to just run and jump into her arms.

NP: It was interesting to hear you say that Trevor Noah’s grandmother inspired her likeness.

AH: That’s true. I was struggling with her likeness. Each time I submitted the sketch to the art director for review she was never quite right. I decided to just take a break. While on my break I ran across Trevor Noah’s grandmother from Soweto and was instantly inspired. I said, “That’s Nana!”

NP: It feels like Nana is alive.

AH: Which was my goal. When I created the illustration with Nana’s tribal markings, I wanted children to see her soul first, how warm, lovable and approachable she was. In essence, I wanted them to be curious about the tribal marks but have a willingness to understand differences that make us unique.

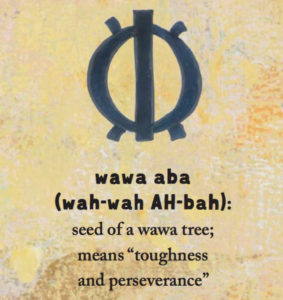

NP: You mentioned that one of the symbols was in the movie Black Panther.

AH: The Wawa Aba. It means toughness and perseverance.

NP: You also said there were some other Adinkra symbols hidden in the book.

AH: Yes, there are. There’s one in particular, the Bese Saka symbol. If you look around the book, you’ll see it in other places. Another hidden symbol is the Nsoromma, which means “Child of the Heavens.”

NP: In your dedication, you mentioned your grandmothers. What do you think they would feel about the book?

AH: I think they would have loved it. They were very supportive of their grandchildren.

NP: So you were illustrating a book about a grandmother, and you’re a grandmother. Were there any parts of yourself that went into the book?

AH: Yes, the big hugs and special table conversations which I and my grandchildren hold dear to the heart.

NP: Let’s revisit your own childhood. When you were growing up, who were your favorite artists?

AH: I was actually an avid book reader in my childhood, art actually came much later in my late teens. As an artist now, I guess my biggest influencers were Charles Alston, Augusta Savage, Romare Bearden, and Charles White.

NP: What was the first piece of art you created?

AH: My first piece of art was a drawing of my first “puppy” love. Long story short, he loved the drawing but not me. My first painting was after my Mom died unexpectedly in 1991. Painting was therapeutic to me, it kept me in a certain mind space. My sister has the paintings from that period in her collection.

NP: Your next picture book is about the legendary Shirley Chisholm, who made a run for the White House back in 1972.

AH: Yes. The title is Shirley Chisholm Dared: The Story of the First Black Woman in Congress, and it’s written by Alicia D. Williams. The release date is fall of 2021.

NP: In honor of Nana Akua, I’d like to conclude with a question about grandparents. They’re venerated in many cultures. Nana and Zura’s relationship embodies this. Do you think grandparents are being more appreciated now that their lives are more vulnerable in the pandemic?

AH: It is my prayer that, in times like these, we recognize and appreciate the people who are most important to us. So, yes, I feel that these moments have caused a new awakening of family, especially our elders.

To view more of April’s fine art, please visit www.justlookin.com

“It’s not only a celebration of difference, it’s a universal story.”

Meet Tricia Elam Walker

Tricia Elam Walker is an award-winning author, attorney, and educator whose work has appeared in The Washington Post, Essence, and other publications. Nana Akua Goes to School is her first published picture book. This interview with Tricia by Nadine Pinede has been edited for length and clarity.

NP: I really appreciated your virtual event with illustrator April Harrison for Politics & Prose Bookstore. How did you get your start in children’s books?

TEW: I always wanted to write. My mother was a children’s librarian in Boston, and she passed the love of books on to us. I remember that when I was around seven years old I wrote something and told my mother, “I want this to be a real book.” She showed me how to sew the pages together so that it would be. What’s interesting is that I made the character a little white girl, because that’s all I had seen.

That sent my mother on a hunt for books with positive images of Black characters. She headed the Boston Public School library program, so she made sure those schools had multicultural books as more of them were published. That became important to me too when I had kids.

NP: What was your journey to children’s books?

TEW: I was a lawyer for many years before I became a writer, but I always wrote on the side. My first book was a novel, and I also wrote a lot of essays, short stories, blog posts, fashion commentary, and other things. It was a long time before I got around to children’s books.

My cousin is the illustrator Ekua Holmes, who’s a Coretta Scott King Award winner. She and I always talked about doing a children’s book together, which ultimately became Dream Street. We sent that around to so many places and their response was these are vignette so maybe it’s a coffee table book, but not a children’s book. We had a lot of no’s for a couple of years. When I linked up with Regina, she saw some possibilities, and we got a book contract with her help. It’s coming out in 2021.

NP: You said it takes a village to create a children’s book. What role did Regina play in that village?

TEW: Regina is everything. What I love about her is she’s herself, she probably thinks about your feelings, but she’s to the point. If she has to tell you, ‘That not good. That’s boring. That’s depressing,” she figures you’re a grown up and you can handle it. Because what she’s saying is, “I know there’s something better in you. I know you can do this.” So she’s everything, first of all because she believed in Dream Street when she saw it, and then she sold it. That was amazing. After Dream Street was sold, and I got the contract for the separate book, Regina would look at what I sent and say, “Nope. That’s not it.” I loved that because it pushed me to be my best self and find the best story in me.

NP: How did Nana Akua’s story come to you?

TEW: I’m a Buddhist, and I was chanting about what story to write because I was up against a deadline. I was at a friend’s house, and he had these African masks on the wall. I just felt the story come to me through the chanting and through the masks. I had to work at it because at first I thought it was the little girl with the facial markings, but after doing some research, I realized it would be an older person.When I initially sent Regina the Nana Akua story, she had ideas about that. She’s the one who got me thinking about using the Adinkra symbols. She’s worn so many hats: She’s been a writer, an editor, and an agent. That’s really helpful. I’m also glad April decided to take her on as her agent, because she wasn’t represented.

NP: What did you most enjoy about working with April?

TEW: In the beginning I wasn’t shown any of the artwork she created for the book. Apparently the publisher purposely keeps the writer and illustrator separate, but eventually we started talking a little bit. I’m not sure how far in that was, but it was early enough for April to have asked me if there were some things I really wanted conveyed. I appreciate that she asked me that. I remember saying the little girl needs to have natural hair. That was important to me. Then April suggested those little afro puff balls. I said yes, perfect.

NP: I had those growing up!

TEW: It was great to have an illustrator who knew exactly what I meant, and who’d had that experience. I also wanted diverse kids, and she did that in the classroom. We didn’t talk about Nana Akua that much, except we both really wanted her to be warm and loving, and she created that.

I already knew April’s work because I’ve had it in my house for over 20 years. I didn’t know it was hers, but I loved it. When the editor sent me some samples of other work she’d done, it was a dream come true. She literally breathed life into the characters that lived in my head. So while we didn’t collaborate all along, she understood what I wanted. She understood my heart.

NP: Have you ever traveled to Ghana?

TEW: I’ve only gone to Senegal. I’m glad you asked that because initially I was going to set it in Senegal because that’s where I’d been. But, through research again, which I’m so thankful for, I found out they really didn’t use tribal scarring. Regina was also helpful with my research. She knew some Ghanaian folk and checked with them, and I had a very good Ghanaian friend who I thank in the book who helped me a lot as well. You want to get it right.

I know that just going on that trip to Senegal—I took my oldest son there—was a life-changer. Just getting off the plane, having people you don’t know, you never met before, say welcome home. I was crying almost the whole time I was there.

NP: When was this?

TEW: In 2004. My aunt was the ambassador to Senegal under Bill Clinton, so we stayed at the embassy, but we’d also go into the villages, and we got to see the different worlds. It was quite an incredible trip. It was disappointing to see women in Senegal who wanted to bleach their skin. That has to do with looking at American culture and thinking that’s it’s better in some kind of way. What I hope is that my kids know: You are wonderful. You are beautiful. You have everything you need. The aura of white supremacy is so heavy, so I think Black parents have to make it an all-out war to fight that with their kids.

I also worked at Simmons College in Boston for a while when I had moved back home before my parents passed away because I wanted to be closer to them. At Simmons I was involved with a program that brought over African students from Mali, Sudan, and other African countries to study in the states. We took them to New York, DC, and other places. It was a wonderful experience that could not happen right now.

NP: Are there any Ashanti traditions you’ve incorporated into your own life? Are there any Ashanti traditions you wish were more widely observed? What life lessons do they offer?

TEW: I definitely feel like incorporating the Adinkra symbols is important to me. When I went to New Orleans, I saw that they were incorporated into some of the ironwork in front of the houses. That blew my mind. I didn’t know anything about that, and now I want to know where else I can find them.

I have jewelry and different objects that have some of the symbols. I like knowing the different meanings and looking at them and having them displayed around the house. Even though my kids crack on having gone through African-centered schools, we did Kwanzaa for many years. I wanted to break them of the materialistic tradition. All those things I feel did pay off. So I think that I’ve tried to incorporate as much as I can.

I think it’s important that the veneration of elders continues. I made sure my children saw how I took care of my parents. I literally picked up and left DC. At the time I was still teaching at Howard, so I commuted from Boston to DC every week for three years. Because I wanted to be there with my parents. I was with both of them when they passed away.

NP: You mentioned the veneration of elders. Do you think grandparents are being more appreciated now that their lives are more vulnerable in this pandemic?

TEW: I think for some people, but I was so disturbed when I heard some governor essentially say it was all right for older people to die to get the economy back on track. And then Mario Cuomo said, “My mother is not expendable.” I love that he said that.

We’ve seen those images of young people on the beaches who were interviewed and said they weren’t worried. They’re young, and they’re not going to get sick. Not caring about whether they could carry that back to someone else. There’s an element of that, but other times I saw people, like some of my students, refuse to go home because they didn’t know if they had something, and they didn’t want to carry it to their parents or grandparents.

NP: Do you think elders are treated differently in different cultures?

TEW: I feel at least in the African-American community, for the most part, I see people really caring, people saying they don’t want to put them in nursing homes. A lot of grandparents are actually raising their grandchildren.

I asked the Boston Globe interviewer how she found out about the book. She’d looked it up, and it reminded her of a scene she’d seen years ago of an Asian woman whose feet were bound. She seemed to be a grandmother, and her grandchildren were helping her walk. Because of the bound feet, it was very difficult. She said that scene stayed in her head for a long time, and my book reminded her of that. I love that, because it was a totally different culture, but she saw the universality in the grandchildren who were so caring about their grandmother.

NP: Your children were in African-centered schools. What impact did it have on your family?

TEW: It was important to me, because I’d integrated a white private school in Boston. In many ways it was very traumatizing for me, even though I got a “good” education. I’ve written a lot about that experience. I knew I didn’t want a repeat of that for my kids.

Early on I felt like I needed to give them a foundation before they ventured into that other world. So I sought out the African-centered schools, and I feel like they did the job that I wanted. Now that they’re grown up and we’re all spread out, we have a Zoom book club. And we’re reading Stamped, by Jason Reynolds and Ibram X. Kendi, which is about racism. We started it before the George Floyd protests, but it’s very timely. Anyway, on the call my son mentioned being teased because they were going to the African school, and I said, but you made it, you came through!

NP: And you have a book club with your kids. How many people can say that?

TEW: It’s great. Especially because my son decided everyone would take a turn leading it. And so to see them decide how they’re going to lead the discussion, it has shown me another side of all of them actually and I feel really proud of them. They really think about what’s going on in this whole situation. My daughter got arrested protesting, and I’m proud of that, too, but that’s another story.

NP: You talked about your mother being a librarian and loving picture books and feeling that they could change the world. What do you think she would most treasure in your book?

TEW: Oh, you’re going to make me cry. I think about her. This book is for her and it’s because of her, and so I think about her a lot and I have one aunt who is my father’s baby sister and the last the last living person in that family. And my mother’s siblings have all passed away. So my aunt represents my mother to me in a sense. And she’s always saying, “Your mother would love this, she’d be so proud.” And I think she would. I think she’d be really pleased that her lessons paid off.

NP: And that you’re paying it forward. What were your favorite books growing up?

TEW: I loved the Amelia Bedelia series, because she was always up to all kinds of mischief. I liked the Madeline books too. Same thing with the Eloise books. All of these had white characters in them, but as Anna Deveare Smith said, we learned to empathize with white characters because we didn’t have anything else. We could feel what they felt and, which is important. That’s why white kids need Black books right now.

NP: That’s crucial. At this moment in history, what do you feel can be learned from your book?

TEW: That’s a great question. This is a really hard moment for me, as I’m sure it is for you. It’s heartbreaking; it’s heart-wrenching. I have two grown sons—Black men. I have a daughter, too. They are forever changed by this. We have a family text and sometimes I dread what I’ll see in the morning. I tell them, “Trigger warning for me, please.” Because I don’t want to see the destruction of Black bodies. I don’t want to see all the different cases. I can only take so much, so it’s a very difficult time.

The YA author Nic Stone wrote an article for Cosmopolitan about how important it is for children to not just read Black books about Black people struggling and overcoming the struggle, but to read about Black children who are doing regular, normal, everyday things. Just living a normal life and/or creating magic.

Nana Akua Goes to School is not only a celebration of difference, it’s a universal story. It has specifics that pertain to Africa and African-American people, but the feeling of loving a grandparent who may look different than others, who you want to share with people, without hurting that grandparent, and not having her talked about: how do you negotiate that? Children want to be loved, they want to be liked, and they don’t want to be different very often. It’s a universal story and that will help with this whole struggle to normalize Blackness.

I’m 66. We don’t know what’s going to happen and how long we have. None of us know. But my hope is there is more time to write more children’s books, and the next time I want to write a story where the children are African-American, but the story doesn’t have anything to do with that: just regular kids, living their lives.

Learn more about Tricia’s work at www.triciaelamwalker.com