An Interview with Derrick Barnes and Gordon C. James

Author Derrick Barnes and fine artist Gordon C. James, both based in Charlotte, N.C., are the creative team behind 2017’s critically acclaimed picture book Crown: An Ode to the Fresh Cut and the just-released I Am Every Good Thing. This interview by Nadine Pinede was edited for length and clarity.

NP: Crown: An Ode to the Fresh Cut, the first picture book you worked on together, has become a modern classic, earning starred reviews and a slew of awards, including the Caldecott and Newbery honors, and the Ezra Jack Keats and Coretta Scott King awards. No small feat for your debut! How did the success of Crown change your lives? Let’s start with Derrick.

DB: Because this was our first picture book together, it seems like we just came out of nowhere. But nothing happens like that. Crown was my eighth or ninth book, and, man, I had been plugging away at this for a long time. I’ve been writing since I was in the fifth grade! It’s been a lot of hard, long nights and tears and wondering should I even continue to create in order to make a living.

To be quite honest with you, 2018 was a blur, and it was probably the greatest year of my creative life. I had gone for six or seven years without a book deal. Being able to travel and landing book deals—it’s been an extreme blessing just to be able to do some of the things that I wasn’t able to do before. We have a pretty large family. You never think about being able to be the head of a family and take care of them by creating stories and creating characters. I don’t think I ever thought about doing that. To be able to do that now is just—I still pinch myself. So, I hope this can continue. I want to continue to make books as powerful as Crown.

NP: Gordon, what would you say? How did it change your life?

GJ: Our paths are pretty similar. Crown was probably my fifth book and I was in a six- or seven-year drought when Crown came up. I had been painting and doing the whole gallery thing. I think the best way to say it is that it really allowed me to support my family. My wife always does really well financially, and when the opportunity to do Crown came up, she was in between jobs. That’s the whole reason why I did the book; it allowed me to be that breadwinner. But almost more important to me than the money was that Crown allowed me to get my artwork in front of an awful lot of people, and share that style, that way of painting, that way that I communicate, with a lot of kids and a lot of Americans. I’m really proud that Crown gave me that opportunity.

NP: You both mentioned periods of drought. During that time, what stopped you from giving up?

GJ: I make artwork because there’s something in me and I have to get it out, you know? I make paintings and if you buy the paintings, that’s awesome. But that’s not why I made them. For me the creative process is not contingent on whether somebody sees it or whether somebody likes it. I would be making things, creating things, no matter what. Whether there is a check at the end of it or not.

I have a large studio now, but back then my easel was right next to our table where everybody ate. We have a small home in the city, and there was a point where it was like, “Oh, your easel’s a little in the way. Do you think you might want to take it down?” And I said, “I can’t do that. That’s crazy talk!” When you’re creative, you create. That’s just what you do, and hopefully your work eventually finds an audience.

NP: Derrick, how did you keep going?

DB: I wholeheartedly agree with Gordon. I can’t remember a period in my life—as a child, as a young adult, or as a man, no matter what my financial situation looked like—that I wasn’t doing something creative just to hold my sanity together, just to keep it together. Even at your lowest point, you wake up and go through your normal routine, and your mind just automatically takes you there to create something. I can’t remember a time when I wasn’t doing that.

Another part of it is that we have four boys, so I know they’re constantly looking at me and paying attention to my work ethic and my drive. I want to make them proud. I want to make my wife proud. I did have a little bit of success for my prior books, and I knew I had something to say. As a Black artist in this country, I think we have an obligation, whether we know it or not, to create something that uplifts other Black folks. If you have something to say, you have a message, you can’t keep that to yourself. I’ve always felt that way.

I’m constantly trying to grow and become a better writer. I’m always excited about the opportunity to get better, to go as far as I can and see how strong my voice can get.

GJ: I have one more thing to say about that. I really believe that you are what you do. There was a point in my life where I was saying to myself, “I’m an artist,” and then there was a point where I looked up and I was thinking, well, I haven’t painted in that long. At this point, I’m not really an artist. I’m a stay-at-home dad. And I love my kids. However, I had to decide: This great and important thing that I’m doing, raising my children, is this going to be the only thing that I do? Or am I going to go back to this easel and be an artist again?

I decided I was going to be an artist, and where there’s a will, there’s a way. Like Derrick said, I want my kids to see me not just being good at what I do: I want them to see me being great. Knowing that you can do these hard things out here in life. It’s possible.

NP: I was listening to a panel on Building Community with the founder of the African American Literature Book Club, and both of your picture books were highly praised. How important has support from the Black community been in your careers?

DB: It means everything to me. During that six-year drought, I worked at the Kansas City Public Library doing outreach. It was a very humbling experience. Sometimes we would do creative writing exercises with middle grade and high school students, and I really learned a lot about myself. I learned a lot about this industry. I realized that I had been trying to craft my manuscripts to appease the gatekeepers at these publishing houses, and most of them are not Black. They don’t have a vested interest in our community.

When I was working one day, one of my sons said, “Daddy, you know what you should do? You should make the Blackest book ever.” That was before I started working on Crown. And I just realized, I’m already not getting book deals. Who am I writing for? I’m creating these stories for little boys like my sons. I’m creating these stories for Black boys and girls, and I just have to put it all out there.

The love that we get for Crown—I get emails from barbers from all over the country, Black mothers, Black educators, and it just feels good. I know that they are my target audience and to get that kind of love back fuels me to continue to write those kinds of stories, create those kinds of characters, create those mirrors for those children to see themselves.

NP: And Gordon?

GJ: It makes me extremely proud. Derrick and I aren’t the only people that make books targeted toward our kids, but there aren’t a lot. There are even fewer that are targeted toward Black boys, like Crown and I Am Every Good Thing. I was an avid reader growing up, but very few of the books I had had characters that look liked me. And even then, you learn later on that a lot of the most popular books, the ones that you loved the most, were not created by Black people. That doesn’t mean they’re not great books. It’s just a fact.

So it feels good, it feels phenomenal, when you go to the schools and you see how much the kids love it. My mother was a teacher, and she taught a lot in D.C. I had a chance this last school year to go back to one of the schools where she taught. I love seeing the looks in kids’ eyes when we show up someplace and talk to them about the book—because a lot of them don’t know that it’s possible that you can do this. It makes me feel good to maybe be the inspiration for that kid who likes to draw or that kid who loves to read and is thinking about writing a story.

NP: In Crown, the barbershop is where the magic happens. Barbershops have also become a part of a mental health movement called The Confess Project, which was created for Black boys and men dealing with trauma and other issues. What role did the barbershop play in your lives growing up?

DB: Man, I remember there were three barbershops that I went to in Kansas City, Missouri. They all had jukeboxes, and they were all filled with classic R&B and blues. They had the Coke machines with the glass bottles. Before they made these fancy seats for kids to sit on, they would put the boxes that the Coke bottles were recycled in on the seat for you. I just remember seeing so many different types of Black man. You could see the garbageman, preacher, dope dealers, you know, guys that were lawyers maybe, all in one spot. And you felt that energy.

When you get that group of Black men together on Saturday mornings from all different walks of life, you just feel like they’re going to solve every single problem that exists in the world. And I got that energy from all three of those barbershops. It’s like our country club, really. I think that energy still exists. When I take my sons to the barbershop—even though I don’t have hair, I shave my own head—I still feel that energy. It’s just so positive and empowering.

NP: I like the description in Crown of the men in the barbershop as “Black angels” ready to guide you.

DB: I wrote that line because barbershops are always right in the thick of the hood, so you never know what you’ll be confronted with when you step outside that door. But I just felt like if you are of that environment, God is going to guide you, grab ahold of you, and take care of you. I used to travel to the barbershop when I was in high school, and it was in the worst part of the city. I used to ride the bus there and I never felt like I was in danger. A lot of that was because my brother is seven years older than I am, and he was always taking me to hang out with him and his friends.

Now when I do school visits, I want to meet people that are at the corner store, I want to go to the schools that people have given up on and meet people that come from the belly of the city. I learned that from going to the barbershop as well, just not being afraid of my people. I love Black people to death, no matter where they live in the city. You learn how to communicate with other men, just by watching them. So, yeah, the barbershop is a magical place.

NP: Gordon, what role did the barbershop play in your life growing up?

GJ: I grew up in the suburbs in Maryland. My father’s a D.C. police officer, and so we would always go to the barber shop in D.C. The first one I remember is Dave’s Barbershop. I got a chance to meet people that didn’t talk like I did, they didn’t walk like I did, and they were always cool—they always accepted me even though maybe I felt like I was different. At a certain point, you know that you’re loved when you go there. It’s a great place.

The barbershop that’s featured in our book is Heads Up Barbershop, and that is on the plaza here in Charlotte, North Carolina. The barber in the book is our friend Reggie, my son Gabriel’s barber.

NP: And you both live in Charlotte.

GJ: Yes, in the Charlotte area. Reggie was nice enough to let me into his shop and agree to be the barber and really give the barbershop that authenticity. What I will say about the barbershop is that it is a safe place. We have a special needs son, Gabriel—he’s on the cover of I Am Every Good Thing—and there are very few places that we would leave him by himself. But the barbershop is one of those places. It’s a place where everybody knows him, where he’s loved. If he has a hard time, somebody’s going to pick up the phone and call us. Barbershops serve these many, many purposes, and you don’t always realize it until you sit back and think about it.

I remember going to the barbershop with my dad. I loved that when I was getting my hair cut, they were treating me the same way they treated my father. My father is a grown man, he’s a big man, in my opinion he’s a tough man. When I sit my skinny butt down in that chair, I’m getting that same conversation that my dad got. They are taking that same amount of time on my hair as they are on his hair. I felt like that was an adult experience that I got to have at a young age.

I see it when we go to Heads Up with my son. Some of those kids, they show up by themselves with the cash, navigating that situation, having that independence. Everybody looks out for those kids. If they’re doing a little too much in the barbershop, one of the older brothers will say “Hey, man, why don’t y’all just have a seat and relax?” They say it takes a village. It’s one of those places where you can actively see the village raising the children.

DB: I wrote that in the author’s note. If you think about it, the barbershop is probably the only place in the Black community, other than church maybe, where Black boys are tended to, where somebody is actually tending to them. Tending to their needs, asking them about their day, and sprucing them up. I think that’s the core of Crown, which is not really about a haircut but more about how much we care about our sons and how much we care about Black boys.

We’re not going to get that same message outside of our families and outside of our community, but I think we need to do everything we can to espouse to the world that you can’t continue to treat our children the way you treat them. That they have value to us. I think that’s the overall message of both of those books, really. That we care about our sons immensely, and we will do anything we can to make sure they’re safe, they continue to grow, and they are loved.

NP: Derrick, you graduated from Jackson State University, an HBCU. How did that shape you as a person and as a writer?

DB: It changed my life forever. I have three close friends that I consider brothers, and those are guys I met at Jackson State. I met my wife there, so that obviously changed my life. But just being on that campus, understanding the history that existed on that campus, and the history of the whole state of Mississippi with regard to the civil rights movement. You feel all of that when you’re down there. Being in that lineage, being a graduate of an HBCU, saying that I came from Jackson State University, it really motivates me. I want to make my alma mater proud and continue to be in that list of alumni that come from a strong HBCU.

NP: How did both of you first meet Regina?

GJ: I can start that one. Derrick and I were working at Hallmark cards, and there was another illustrator, Shane W. Evans, who had done a few books already. It was something he’d been doing on the side. He got an offer for a book that he couldn’t do, and he asked me if I would be interested in it. I said, “Sure,” and he introduced me to Regina. Shortly thereafter, I sent her some samples, and she agreed to represent me. That was almost 20 years ago.

NP: How did you introduce Regina to Derrick?

DB: I just got bitten by the bug, talking to all the other writers and artists, everyone doing something outside of Hallmark—which is a blessing of a job, to come right out of undergrad as an artist. I remember that letter saying that I got the job. The salary was $30,000, and I was 23, and I was like, man, “I’m about to move Mama out the hood.”

NP: And weren’t you the first full-time Black male employed there as a copywriter?

DB: I was hired as the first Black male writer in the history of the company. There had been other Black men that wrote for them, but they had never hired a Black man to be a full-time copywriter. I just got bitten by the bug, and I started writing short stories and poems while I was at work and looking into how to land a publishing deal. I was sending out letters to literary agents, and I remember Gordon coming by my cubicle—I had no idea that he had an agent or that Shane had an agent—and he just said, “I can connect you with my agent.” It was as simple as that. I gave Regina a few samples of my short stories, and we agreed that she would represent me. That was in 2004, and we’ve been together since.

NP: How has she been involved in your collaboration and in the way you two work together?

DB: I love that woman to death. Thinking about all of these peaks and valleys I was telling you about, she’s been there through all of that. She’s been there through the birth of three of my sons. She’s just such a brilliant woman. I love the way she’s able to compartmentalize and how ideas just pop into her head so quickly. Gordon and I talked about this before—sometimes you think that no idea that you come up with is going to be good enough. She’s always going to have something to say about one of your ideas. That’s just the way her mind works. It’s not about her stepping on your ideas. Her mind is always somewhere else, and I think you need that sometimes. As artists, we do a lot of work by ourselves, so you can become convinced that you have the greatest ideas ever, or what you just created or what you just painted is the most beautiful thing ever. And I don’t have a live-in editor, so her ideas are valuable. Whatever we come up with, she takes it to the next level.

And I always feel like she’s constantly working, which allows me to focus on my craft. I’m able to just write. I appreciate her so much.

GJ: I feel like it’s helpful to have that person in your creative life that is thinking about the big picture. She’s thinking about the entire book. She’s thinking about the body of my work. She’s thinking about where it can go next. She’s had experience with other illustrators, with other creatives. I have ideas, but she knows what the possibilities are, because she’s been there, and she’s seen it before. It’s never her first rodeo.

Hopefully Derrick and I will be moving into some spaces where we’ll be doing some ridiculous things that might be her first rodeo, and that’ll be fun. We’ll navigate all that stuff together. But I have no idea what those things might be.

NP: Derrick, can you tell me about the dedication to I Am Every Good Thing? You’ve said that this book was both fun and painful to write.

DB: I started writing the book when George Zimmerman got off for murdering Trayvon Martin. You start thinking about ways to heal from this and ways to explain it to your sons, and why this has been allowed to happen in America for eons now. I started writing a poem about how much we love our son, and I didn’t finish it.

I picked it back up after Mike Brown and Tamir Rice were murdered. One of the things I started noticing was every time a police officer or armed adult killed an unarmed Black boy, there was always this narrative that was created, trying to paint the boy in a negative light. You know, maybe he dabbled in marijuana, maybe he got suspended, and in Mike Brown’s case there was the whole cigarillo incident. And it’s all a sick attempt to, I guess, justify the murder of this child.

You started seeing this pattern constantly, and so that’s the genesis of me dedicating this book to all these young men. I hate that we have to create books like this. Imagine being in a world where we don’t have to create artwork that affirms the existence and the humanity of Black boys. We’re in a pandemic right now, there have been protests for months, and the same thing continues to happen. In every single city in this country. I want one day, to be honest with you, not to have to write books like this. But until the world changes—and hopefully these books help move things in that direction—I think we’ll continue to create art like this.

NP: Gordon, what about your dedication?

GJ: My dedication is to my son, Gabriel, and all the little brothers like him. With Gabe being autistic, he speaks but he doesn’t speak quickly. He doesn’t respond quickly. Derrick has always said, and I agree, that one of the big reasons for books like this is that they humanize our boys and they let people see them as people. You see those stories on the news asking, “Why didn’t he comply?” What sometimes is lost is that not everybody can comply. If you pull out a weapon and you start yelling at my son, he’s probably just going to wave his hand and start rocking back and forth. It’s going to be entirely too much. I’m hoping that a book like this lets people see our Black boys as human and maybe gives someone a little bit of patience, because sometimes you have no idea what’s going on.

NP: Were there any special challenges you faced when you were bringing Derrick’s poetry and words to life in illustrations?

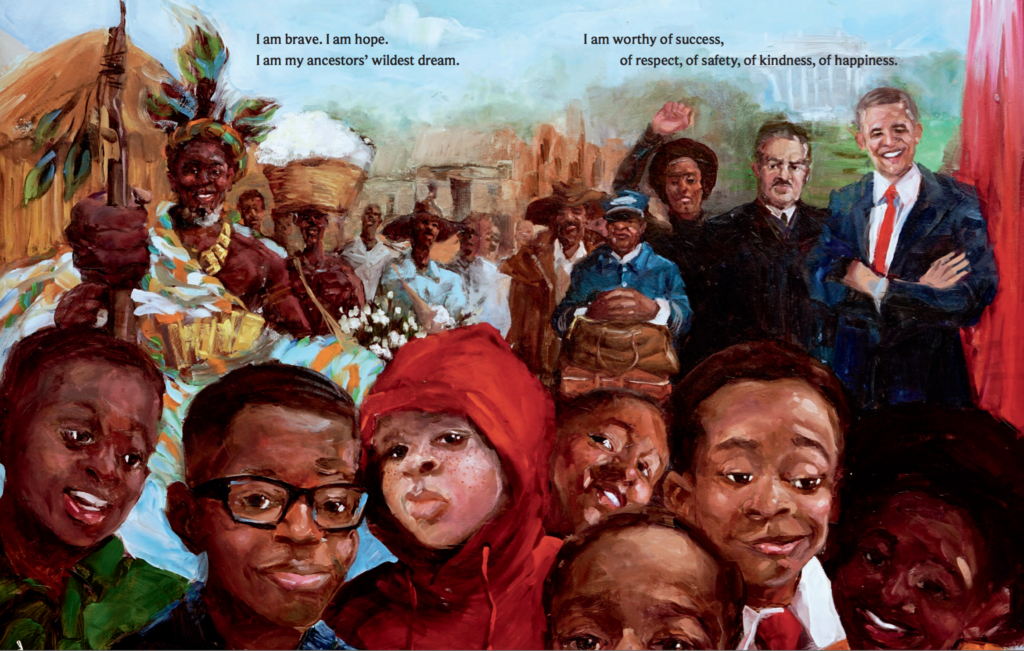

GJ: If there was a challenge, it was that the story is very sweeping, and there are a lot of different ways to think about it. The way that I thought would be best is, instead of following one boy through the story, for it to be a celebration of boys. That is why you see some people, like my son and a couple other kids, pop up over and over again throughout the book. And then there are boys of different ages, different skin tones. They look like they could come from different places in the country, different income levels, and different family situations. I wanted to show the richness and the depth and the diversity of our culture as a whole, and of our boys in particular.

And I wanted to communicate that they belong wherever they want to go. They’re entitled to their space, to their life, and to this life—this American life, and everything it has to offer. They should not be limited by who they are or where they’re from. I just wanted them to see the possibilities of life, because growing up where I grew up, and then going to high school where I went to high school, and then living where I did in college, I realized that I can be in all these different spaces, and there are just tremendously wonderful things about all these spaces.

If you’ve never been to a corner store in the hood, you’re missing out. If you’ve never gone swimming at a country club, you might be missing out. If you’ve never been to a museum, you’re missing out. And if you’ve never been to a barbershop in the hood, you’re missing out. What I find is that people devalue certain parts of Black life, and I wanted to show the value of all the unique and different things that we do, and let our boys know that they can do anything they want to do.

DB: That’s one of the things I really love about the illustrations. You have Black boys in these spaces, and they are everywhere. They exist everywhere, and they’re able to move freely everywhere. Just the idea of that, freedom within the Black mind, to know that you are able to go and exist in different places and not only be there but be happy. These boys are everywhere, and they have smiles on their faces, like, “We are here. And we belong here.”

NP: Derrick, I wanted to ask about the page where the boy says, “Sometimes I’m afraid.” And the way the book ends with repeating the worthiness of being loved. How did you come to those two powerful moments?

DB: I was raised in a single-parent house. My mother worked her tail off. I had four uncles who were very strong father figures, and my brother is seven years older than I am, so he was a very strong male role model as well. But there’s nothing like having a dad there. A dad, somebody who is with you on a daily basis.

I was blessed enough to be the father of four boys. So I think about their faces when I’m trying to have these conversations with them about real American history, about the history of Black people in this country. When I’m trying to have a conversation with them about these police brutality incidents, I think about the look in their eyes that says, “I don’t understand why these people would hate me so much.”

I think it’s our obligation to frame the world that they’re going into very meticulously. I don’t want them to have any kind of fear to achieve, or to go in those spaces that I just got through talking about. I want them to know what’s awaiting them. You understand your history, and the genealogy, and why things are the way they are, and then equip them with tools to achieve the goals that they set for themselves.

It is a very tricky balancing act: to make them aware of the pitfalls that they’ll face once they step outside of our door, but also give them the confidence and the intellect to accomplish anything that they want to. You’re going to feel fear when you don’t quite understand the whole background of America, how we got here, and why people think the way that they do. I love one of those last images when you have all those Black boys looking out, and you have all the ancestors standing behind them.

You know, I had to fight for that last line because the editor thought it would be too much to repeat “I am worthy to be loved.” I explained to her—and she understood, that’s why I loved working with her—that in the Black community, with art and music and gospel music especially, refrain is important. It’s just as important as the first time you say it. Repeating things two and even three times adds an exclamation point. “I am worthy to be loved.” I wanted to repeat that one more time so that it echoed, and it’s the last line that will be read and it will stick in that child’s brain forever. I am worthy to be loved.

NP: It needed that refrain.

GJ: It’s cultural. I feel like it’s one of those things that when you read it, our people are going to get it. That’s not going to be an issue. The people who the book is for are going to understand it, that’s for sure. That’s why it’s important to have Black creators, because these are things that we know.

NP: You’ve both mentioned how vital it is that children’s books show Black boys engaged in everyday life. Why is this important to counter dehumanization?

DB: If you’ve lived most of your life viewing other human beings through the lens of a stereotype and not being equipped with either life experiences that put you in contact with these people or the historical context of where these people came from and how they came to be, and you only function off of those stereotypes, you already have a preconceived idea about them. They always paint our boys as having a super-human strength, being great athletes, and being violent, those kinds of things. And when you have those stereotypes in your mind, I think it’s almost impossible for you to see them as being human or being like your children, being like your nephew or grandson.

It’s imperative that, as we continue to create this work, like we did with Crown and I Am Every Good Thing, we make sure that we don’t go overboard with the idea that we are human. We just paint a real-life picture. We were both Black boys at one time, we are raising Black boys, and we are not a monolith. Gordon and I come from two different backgrounds, but here we are, ending up in the same space, both creating artwork for the same reason. It’s imperative that we paint the picture of our sons just being as they are. I’m tired of trying to prove our humanity to people who don’t want to see it in the first place. But I think it’s important for those people who are trying, and it’s definitely important for Black and brown boys to continue to boost up their own self-worth. Hopefully these books do that.

GJ: I think that’s important because there are all these crazy stereotypes, like we don’t feel pain the way other people feel pain. That is ridiculous. I don’t know if Derrick has experienced this, but in my professional life, I’ll get a compliment like, “Oh, the way you emote, I can just see how you feel your way through this work.” I had to say to one editor, “You know, I went to a really good art school, and I am a classically trained painter. I don’t just emote my way through these things.”

I feel like it’s important for us to be seen as full people and for us to get to the point where even the compliments that people give us don’t take things away from us. If you imply that we are just these super-talented people, the flip side is implying that we don’t have to work as hard as other people because we’re born with this thing. I just don’t feel like that’s the case. If you see somebody and he’s a great athlete or he’s a great scientist, he’s not just born brilliant—he has put in that work too. We are full people like you are full people.

NP: Can you give me a sneak preview of an upcoming project? You mentioned a Netflix project.

DB: The trailer was officially released for the Netflix project, which is called “Bookmarks: Celebrating Black Voices.”

GJ: As part of the [Bookmarks] series, Crown: An Ode to the Fresh Cut is going to be read by the young actor Caleb McLaughlin from “Stranger Things.”

NP: Any other upcoming projects you’ll be doing together?

DB: We are on a contract to do a nonfiction book for Kwame Alexander’s imprint Versify about Black American athletes throughout American history who have protested. The tentative title is Do it for the People and it’s maybe 15 Black athletes who have stood up against racism and have sacrificed their careers and lives.

That’s what we have coming up next together, but both of us have a multitude of projects individually. We’ve had so much success with Crown that I feel like both of us are offshoots of each other. So he may be working on a bunch of projects I don’t even know about, but I want all of them to win because of what we created with Crown. I think it’s going to probably be that way for the rest of our careers. You want each other to win.

I have two other graphic novels coming out, and I just signed a two-book deal with Penguin. I have a sports series called Who Got Game? The baseball book came out this past March, and there are two more books coming out in that series. I have some animation projects on the table. That’s my ultimate goal: I want to get into animation, television, film. And I’m working on a middle-grade novel right now.

GJ: Right now on my easel I’m working on a book in a new medium, chalk pastels, which I think is looking really good. It’s called Just Like Jesse, by Paula Young Shelton, and it is about Andrew Young when he was a young man and how he was inspired by Jesse Owens. I’ve also started work for a book about Thurgood Marshall, written by the queen of the children’s book biography, Carol Boston Weatherford.

NP: During your time promoting Crown and I Am Every Good Thing, was there a question that you wished someone would ask you that has not been asked yet?

GJ: I think the best question that that no one ever asked me, because the book has been so well received, is if you had to do it again, what would you do differently? As an artist, ever since high school, you’re doing art, you get done with it, you sit down with your teacher, you have that critique, and all through college you’re just used to that critique period. And when you get out on your own, you do this work of art or this book and you love it, because everything created is a moment in time. It is the best that you can do at that moment in time, and you’re very proud of it. But by that same token everything can be a little bit better and I’m always thinking about what I could do to improve the next project. So that is a question that no one has ever asked me because everybody loves the book. But I think about that after every single project.

NP: Derrick, would you do anything differently with I Am Every Good Thing if you were writing it today?

DB: In regard to writing, there are a million different ways that I could go back and craft this story. But your finished product is what was meant to be. I want to grow from whatever I did last and just leave whatever that was where it is. So I don’t think I would do anything different. I feel like we got spoiled with the success of Crown and you think that every project from that point on is going to be like that and it may not be. But the same type of work and expectations that we put into Crown should go into every single project after that. I know what the possibilities are, so I want to put that same type of passion and energy in everything that I work on post-Crown. You want your work to touch as many people as possible and really have the feeling that it changes people, that it makes people different after they have a chance to see or experience your work. Crown took me to a different level as an artist, so I just want to build on that.

NP: Thank you. Is there anything that you want to add?

GJ: When I work on these books, I try to make every illustration look like it could hang on a wall in a gallery somewhere. I want the words and the illustrations to mesh really tightly together, to fit like hand in glove. And I feel like we’re in the same place, where we want to take the picture book to a level that maybe people haven’t seen. That’s the overall goal. I think what makes us work well together is that we want to be not just good at what we do but great at what we do. That’s what the public deserves and we both work very hard to give them our absolute best. And that attitude, when we come together, makes for what have turned out to be really good books.

NP: Phenomenal books. It’s been such a pleasure talking to both of you. I admire the work that you’re doing. Thank you for putting that out into the world and giving that as a gift to the world.